Seaweeds

Algae are the original primary producers responsible for the oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere, absorbing more carbon dioxide than the Amazon. Micro- and macroalgae therefore offer a ready-made solution to restore Earth’s climate to pre-industrial levels.

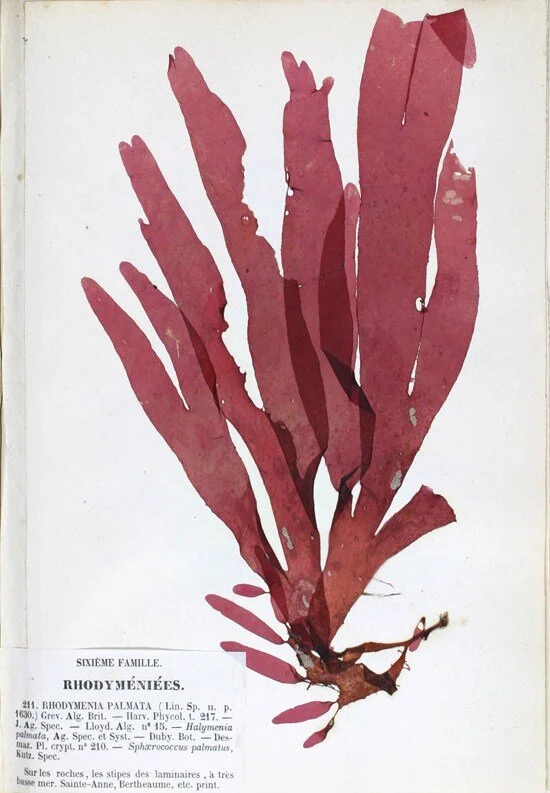

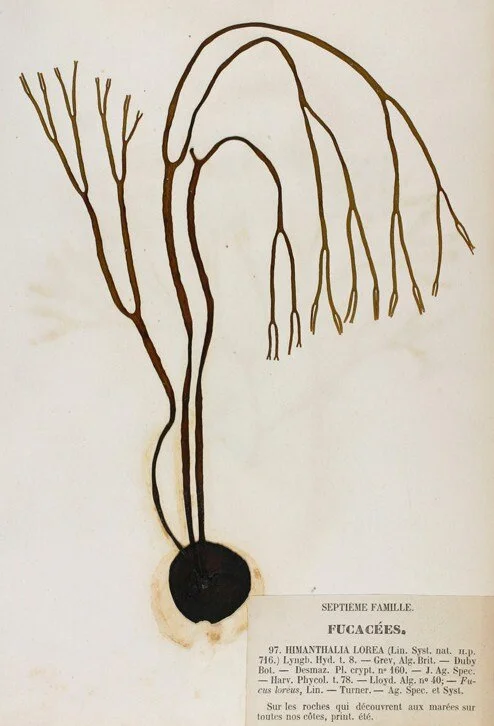

Seaweed was once a major industry in the British Isles. Its many applications are even more relevant today. Besides the many market opportunities, seaweed is a keystone species, providing ecosystem services such as habitat for juvenile fish, carbon storage, oxygenation, storm surge protection and ocean deacidification.

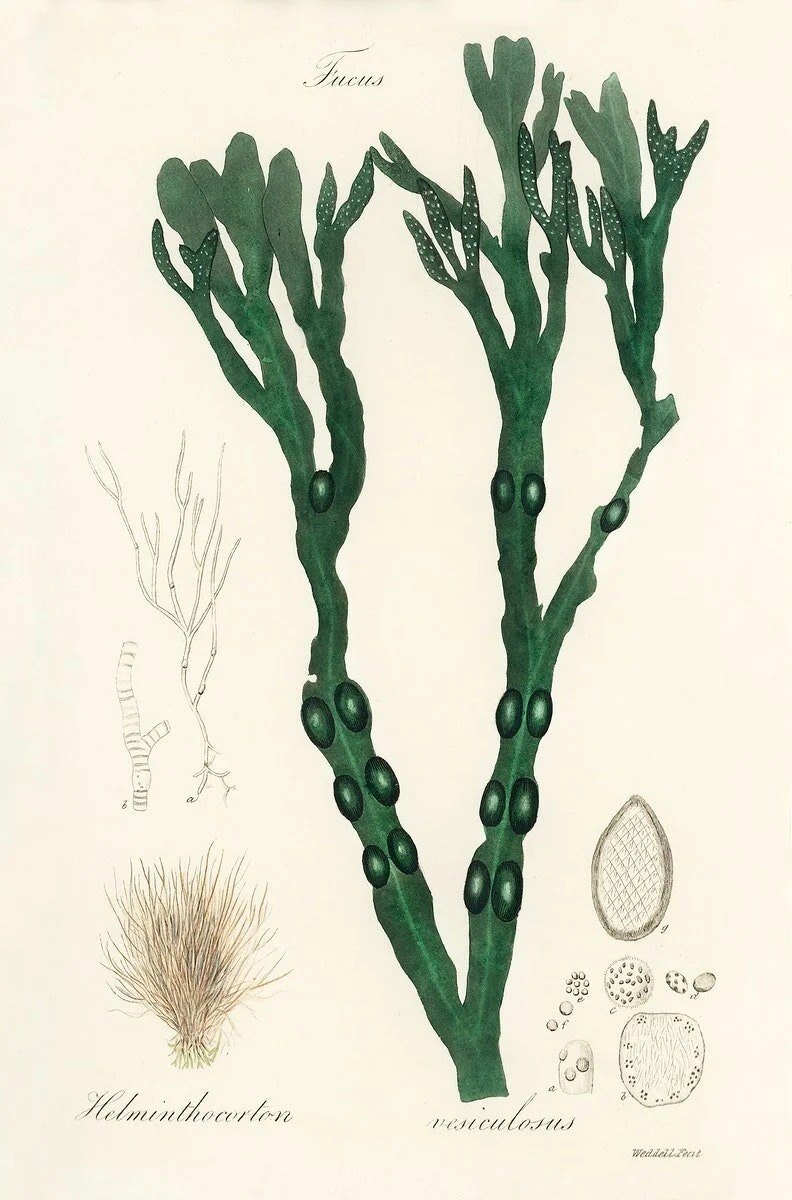

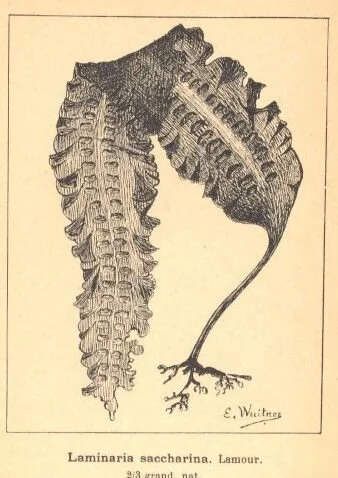

Seaweed has huge potential for multiple market applications: from high-value pharmaceuticals to cosmetics to food, bioplastics, feed and fertiliser. These require either basic (e.g. drying) or more advanced biorefinery technology (e.g. hydrolysis or fermentation) to extract the valuable compounds like pigments, alginate, carrageenan or agar. As service providers to multiple industries, small-scale biorefinery plants will be the key in kickstarting a new seaweed bioeconomy.

The nutritional benefits of seaweed are still being discovered, but the signs are looking good for cardiovascular and gastrointestinal functions, helped by boiactive compounds like vitamins, minerals and omega-3 fatty acids EPA & DHA. The taste is characterised by 'umami': 'the fifth taste dimension' - soy sauce being another example - which adds a healthy, savoury boost to food. In other words, it’s your body’s way of telling you that what you’re eating is good for you.

Still, like everything in the modern world, it’s not always that straightforward. Just as you wouldn’t eat lettuce growing out of a rubbish heap, you should exercise the same caution with seaweed. Do your homework, stay away from sewage pipes and avoid beach cast seaweed. Spring tides are both the best and the most dangerous time to harvest seaweed. Check the local tide timetables online, take a friend or let someone know where you’re going beforehand so you don’t find yourself all at sea.